Gujarati Pulp Fiction: A Note from Our Translator

In this post, Vishwambhari S. Parmar, the primary translator for our Gujarati Pulp Fiction anthology, talks about her experience growing up biliterate.

Even though I grew up in Gujarat, in a town and a family that spoke Gujarati, I would never have taken to reading Gujarati books had it not been for my grandmother -- her enterprising nature, her disciplinarian attitude, and her disdain for the British and their literature. I am more fluent in Gujarati than in Hindi, even though I formally studied it only for four years in primary school. And it’s not because it happens to be my mother tongue or that the state board curriculum takes linguistic education more seriously. It is because my grandmother, disappointed when we were admitted to the only English-medium school in town, took it upon herself to impart the knowledge of our language and culture. And a major part of that process was reading Gujarati literature.

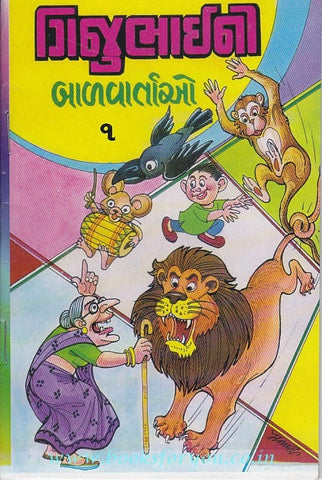

Reading was a mortifying ordeal, in the beginning, at least; for my grandmother would sit me down, hand me a book, and forbid me from getting up till I was done reading it out to her. By the time she began trusting me enough to finish a book, I had developed the compulsive need not only to read anything and everything that I laid my eyes on, whether Gujarati or English – even the nutritional information on empty Frootie packets – but to read it out loud as well. (Librarians don’t generally like me much.) We never really bought books till my early teens and by then I had read all the children’s storybooks from back when my grandmother was young – some forty-plus books from some eighty-plus years ago – twice over, and was moving on to the more grown-up stories.

Gijubhai's Children's Tales

Collection of Funny Stories, by Gijubhai and Taraben

When we moved away to a bigger city, and a better school, I no longer felt compelled to read Gujarati. A godawesome library, with English books aplenty, and teachers who always praised well-read students quickly changed my language preferences. I no longer read Gujarati books for pleasure, except two or three storybooks every summer when we went back home.

And so, in my memory, the Gujarati language and its literature are inextricably linked with my hometown, particularly with my grandmother’s makeshift library-cum-archive of century-old books and half-century-old newspaper clippings. The room carries a scent of old, a sense of age, and fittingly so. For Gujarati literature always had a timeless feel to it--a timelessness that can sometimes be stifling.

My grandmother has always had a deep hatred for the English language. It makes slaves and servicemen out of you, she says, it teaches you all the wrong things. (In her defence, the covers of my grandfather’s James Bond novels were pretty scandalous!) These ideas are pretty common amongst Gujarati readers. All the Gujarati literary criticism I had been exposed to never seemed to move beyond a simplistic concern for liberal humanistic values. A “good” Gujarati novel must evoke the higher ideals of goodness, truth, beauty and love. It needs to teach you something, make cultured individuals out of you, ingrain the history of this glorious land and its valorous heroes.

Even in most romances, these ideals loom larger than the lovers: they are stories of great sacrifices, of courage and loss. Courtship is long drawn-out and subdued, without even a hint of salaciousness. My teenage curiosities could not have been fulfilled by reading “respectable” Gujarati novels. Which isn’t the primary reason for my preference for English books, I’ll have you know! But English seemed to have so much more to offer: so many varied cultural experiences, not only from around the globe but from other worlds as well--like those balanced on a giant tortoise floating through space. There were quests to embark on, parties to attend, mysteries to solve, disbelief to suspend. I was a traitor to the Gujarati cause, in my head. I was a failed Gujarati, with my unusual accent, hatred of the music-and-dance performances during Navratri, and deliberate distancing from cringeworthy pop-culture stereotypes.

Fast forward to the summer of 2020. I was back home after my first year of college and looking for ways to ignore the uncertainty of the pandemic. I picked up Bachubhai Shukl’s Adhuru Swapna, a science-fiction-tinged capitalist manifesto where the benevolent scientist working towards the eradication of global poverty dies in an accident caused by the protagonist, who inherits all his scientific discoveries and a massive industry, gets the girl, and the happy ending that our gentle scientist had deserved. And we are left wondering what the author’s motives were! Oh, and it had a passable hurt-comfort sort of romance too. (Well, it was mostly a lot of fuss over a grazed cheek but…. overactive hormones!)

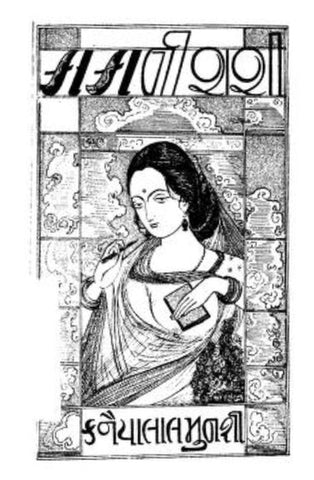

My next read was Kaka ni Shashi by Kanhaiyalal Munshi, a play about a misunderstood bachelor who finally confesses his love towards an orphaned girl he had brought up. (Nothing problematic about that one!)

Kaka ni Shashi by Kanhaiyalal Munshi

These were my first encounters with the less-than-wholesome side of Gujarati literature. They were a huge leap away from the moralistic novels that I was used to. Far from teaching me family values and patriotism, these books seemed to indicate that betrayals, deceitfulness and predatory relationships seldom go unrewarded. I was stupefied by this dark side of Gujarati literature that I had stumbled upon--but also fascinated. There were possibilities waiting to be explored.

Then in May 2021, I started an internship with Blaft Publications, a publication house that has brought out English translations of pulp fiction from various regional languages. They were interested in exploring the area of Gujarati pulp, and we had a lot of fun reading, researching, and discussing various books and stories for the next few months.

Whether due to the general snobbishness of literary circles or the lack of knowledge about genre fiction in the mainstream, most Gujaratis – including laypersons and academicians – are reluctant to even admit that Gujarati pulp fiction exists. Even books whose content might be downright scandalous (such as Kaka ni Shashi) are privileged over penny novels and attributed high literary values.

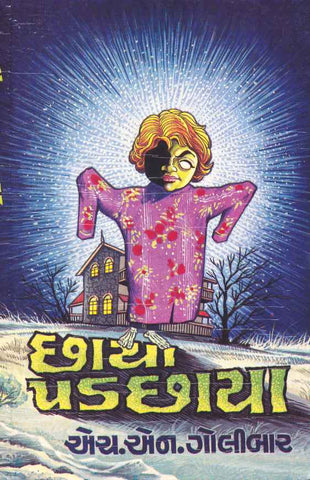

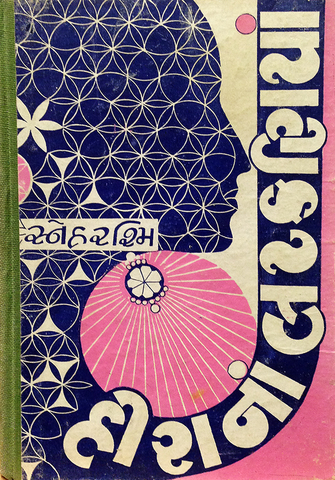

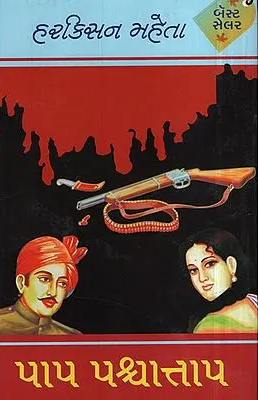

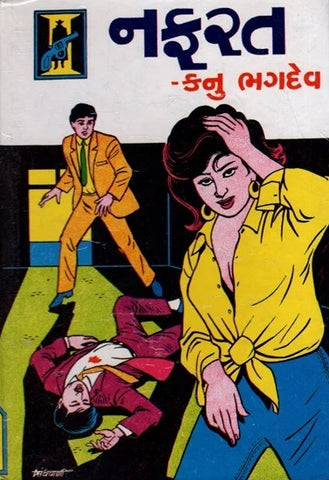

Soon, though, scouring the internet, I discovered many authors like H. N. “Atom” Golibar, Vibhavari Verma, Bansidhar Shukla, Ekta Nirav Doshi, Harkishan Mehta, Ashwini Bhatt and Kanu Bhagdev, who have made major contributions to Gujarati adventure, crime, horror, and science fiction. I came across stories of interplanetary adventures, reformed slave traders, and equine romances (more on that last one here. Content warnings apply!) I discovered that the notable literary figure Varsha Adalja had penned some early novels full of crime and suspense, before her writing career veered towards more “serious” subjects.

Leader by Kanu Baghdev

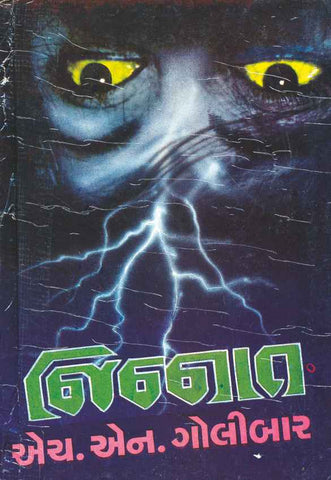

As for H. N. Golibar, one of the best-known pulp writers: his creative process is just as intriguing as the stories he weaves. His plots are often inspired by real-life reports of paranormal encounters, whose subjects – be they ghost, demon or jinn – are immortalised in the vividly illustrated covers of his novels, which take a hold on the imagination long before one begins to read. One reader told me that the collections of Golibar's books in the Junagadh library would always be in tatters: readers would rip away the book covers to use them as Christmas decor, while others would tear a few pages from the middle, doubling the suspense of the narratives.

Jinnaat by H. N. Golibar

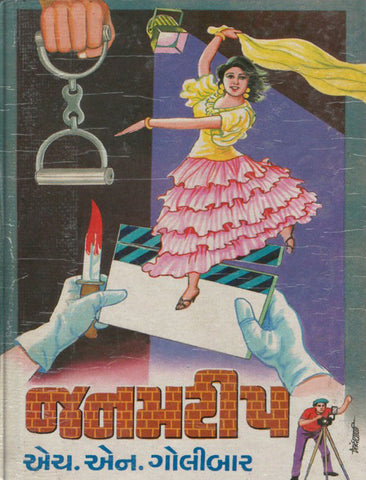

Janamteep by H. N. Golibar

The novels by these authors, though commonly denigrated as sensationalist, are simultaneously ultra-popular. “Ultra-popular” may not actually mean much in terms of book copies sold – 5000 is considered a good number – but it turns out that the readership is much higher in the periodicals and newspapers where the stories are originally serialised. Magazines like Mamata and Chitralekha and dailies like Sandesh and Divya Bhaskar have always provided a ready audience -- a mix of critics, intellectuals, housewives and elderly people. (Recently, many authors have shifted exclusively to the online publishing scene, either on the subscription-based Matrubharati app or Kindle ebooks.)

I've read fantastical tales; tales that intrigued and shocked and terrified; and also some tales that made me want to die of shame. Gujarati literature is no longer tediously wholesome for me, and thankfully so. I understood that a book need not concern itself with higher ideals for it to be “good”. Nor is a book necessarily trashy if it’s about a scandal or a heist, with a murder or two thrown in. All a book needs to pass the test is to be immensely enjoyable.

Spending the last few years reading Gujarati genre fiction felt like coming back home, to something familiar and ancient. But it has also been like embarking on a journey of discovery and exploration.